When Nadine Burke Harris began her career as a pediatrician, she considered trauma and adversity as two things to be handled outside of the doctor’s office.

“I viewed these things as I was trained to view them — either as a social problem or as a mental health problem,” she said in a TEDMED Talk about adverse childhood experiences. External link In both instances, she would refer the patient to social or mental health services.

After finishing her residency, Burke Harris worked for a new health clinic in a severely underserved neighborhood. She noticed a disturbing trend in the number of children who had experienced extreme trauma, and she couldn’t shake the feeling that there was a connection between their health and their environment.

“It felt like something else was going on,” she said.

In 1997, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Kaiser-Permanente released a study examining the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and how they affect physical health, External link confirming what Burke Harris had expected: Experiences of early adversity were linked to poorer health outcomes among adults. The study sparked countless initiatives to help prevent ACEs before they happen and build resilience among children who are at risk for adverse experiences.

Prevention is a step toward addressing this issue; however, there are still adults with ACEs who are currently experiencing the repercussions of early trauma, including mental health issues and chronic disease.

How Do Adverse Childhood Experiences Affect Health in Adults?

Adverse childhood experience (ACE), a term coined in that 1997 study, is now universally recognized in the public health sphere. It is used to describe all types of abuse, neglect, and other potentially traumatic experiences that occur to people under 18.

According to the CDC’s resource page for ACEs, External link childhood trauma has been linked to risky health behaviors such as smoking and substance use, chronic health conditions ranging from cancer to diabetes, and early death. Individuals with ACEs are also more likely to have what the study refers to as “low life potential,” meaning they have lower high school graduation rates and academic achievement and experience more lost time from work as adults.

The scientific reason why individuals with ACEs are at higher risk for these issues can in part be attributed to the way early experiences of adversity affect brain and body development.

“It affects areas like the nucleus accumbens, the pleasure and reward center of the brain that is implicated in substance dependence,” Burke Harris said. “It inhibits the prefrontal cortex, which is necessary for impulse control and executive function, a critical area for learning. And on MRI scans, we see measurable differences in the amygdala, the brain's fear response center.”

These changes in brain chemistry can make an individual more likely to engage in high-risk behaviors External link such as the use of tobacco and alcohol, which are associated with physical health risks like cancer and cardiovascular disease. But even when people with ACEs abstain from high-risk behavior, the effects ACEs have on brain development can still cause physiological changes that result in a decline in health.

One example is the toxic stress that comes with experiences of childhood trauma that in turn produce poor health outcomes. External link The constant presence of chemicals such as adrenaline and cortisol heightens blood pressure, weakening the heart and circulatory system. These hormones also raise glucose levels, which can lead to type 2 diabetes and increase cholesterol. Constant stress can cause the adrenal glands to give out, eventually producing immune system issues. As a result, individuals with ACEs are more likely to experience a host of chronic illnesses in adulthood.

Health Conditions Associated with ACEs

Autoimmune disease: Among patients with lupus, 63 percent reported having one or more ACE, and nearly 20 percent had four or more ACEs.1

Cardiovascular disease: Research has shown a strong association between exposure to ACEs and cardiometabolic outcomes, including heart disease, hypertension, and obesity.2

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): In a study on ACEs among individuals with COPD, after controlling for smoking and other risk contributors, the risk for COPD increased as the number of ACEs increased, suggesting that ACEs were an independent risk factor.3

Diabetes: ACEs exposure increases the risk of type 2 diabetes by 32 percent compared to patients with no ACEs.4

Cancer: ACEs strongly predict behaviors that increase the risk of adult cancer.5

Depression: Having at least one ACE is associated with almost three times the odds of depressive symptoms among individuals reporting poor perceived social support.6

Substance use: According to a 2018 study, adults who experienced household abuse were 30 percent more likely to binge drink alcohol than the general population.7

Who Is Affected by Adverse Childhood Experiences?

No one is immune to ACEs. The original CDC and Kaiser-Permanente study examining the prevalence of ACEs and how they affect physical health showed participants across different backgrounds had experienced traumatic events in their youth.

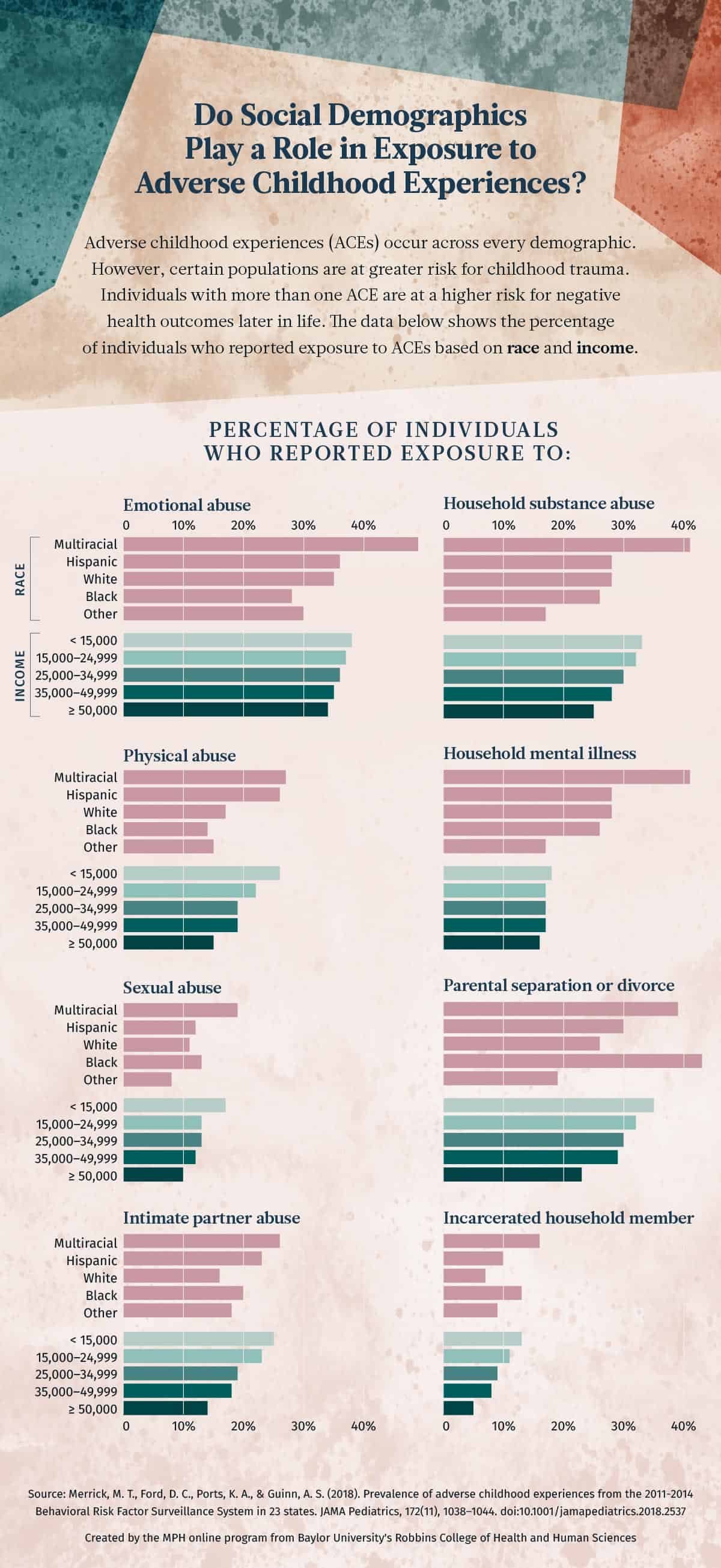

However, a 2018 study on the prevalence of ACEs External link found that certain minority groups were more likely to have them than the general population. Based on the data, race and socioeconomic status were among the factors in determining the likelihood of having at least one ACE. The average number of ACEs among black, Hispanic, and multiracial individuals were 1.69, 1.8, and 2.52 respectively, compared to an average ACE score of 1.52 among white participants. Individuals with a household income of less than $15,000 had an average of 2.16 ACEs, a number that steadily decreases as household income increases.

A 2018 study examined prevalence of ACEs in adults across multiple backgrounds. Researchers found that certain minority groups were more likely to be exposed to certain ACE categories. Black, Hispanic, and multiracial individuals were more likely to experience parental separation or divorce and the incarceration of a family member than white individuals. Multiracial populations and those with a yearly household income of less than $15,000 had more exposure to all ACE categories than other groups across the board. Go to tabular data at the bottom of this post about the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences by race and household income.

Overcoming the Physical Health Risks Associated with Childhood Trauma

Preventive care to mitigate the chances of children having ACEs is a critical step in combating this public health issue. However, steps still need to be taken to provide care for adults who have already experienced trauma.

Integrating screenings for ACEs into clinical services is one way to identify risks for conditions associated with traumatic events. This information can be used to provide better care for these individuals.

What Is an ACE Score?

A person’s ACE score can be determined using a screening survey that was a part of the original study conducted by the CDC and Kaiser-Permanente. It comprises 10 questions that can be asked to determine this score. For each “yes” answer, one point is added to the individual’s score.

- Did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often: swear at you, insult you, put you down, or humiliate you? Or act in a way that made you afraid that you might be physically hurt?

- Did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often: push, grab, slap, or throw something at you? Or ever hit you so hard that you had marks or were injured?

- Did an adult or person at least five years older than you ever: touch or fondle you or have you touch their body in a sexual way? Or attempt or actually have oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse with you?

- Did you often or very often feel that: no one in your family loved you or thought you were important or special? Or your family didn’t look out for each other, feel close to each other, or support each other?

- Did you often or very often feel that: you didn’t have enough to eat, had to wear dirty clothes, and had no one to protect you? Or your parents were too drunk or high to take care of you or take you to the doctor if you needed it?

- Were your parents ever separated or divorced?

- Was your mother or stepmother: often or very often pushed, grabbed, slapped, or had something thrown at her? Or sometimes, often, or very often kicked, bitten, hit with a fist, or hit with something hard? Or ever repeatedly hit over at least a few minutes or threatened with a gun or knife?

- Did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic, or who used street drugs?

- Was a household member depressed or mentally ill, or did a household member attempt suicide?

- Did a household member go to prison?

One way these screenings can be incorporated for risk assessment is through primary care, according to a report on the health effects of ACEs in The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. External link

From the article: “Although there is no doubt that it is easier to treat the presenting symptoms rather than addressing the root cause, empowering patients to see the connections of their whole lives may well enable deep healing.”

This is particularly important for populations experiencing health disparities as a result of factors such as race or income level.

In addition to primary care, screening individuals seeking specialized care has proven to be useful for addressing health risks associated with ACEs. For example, a study on using ACE screening for substance use recovery patients External link showed that all of the participants had experienced at least one ACE — and 82.8 percent reported six or more ACEs. This information was then used to identify additional interventions needed for patient success.

When equipped with this information, health care providers, counselors, social workers, and other professionals working with adults who have experienced ACEs can provide better treatment at two different phases:

- Secondary prevention is the stage where teaching resilience and addressing potential risks can help adults who have not yet developed serious health conditions. The report on the health effects of ACEs in The Journal for Nurse Practitioners External link recommends practicing mindfulness through activities such as meditation and yoga, as well as therapy when needed.

- Tertiary prevention is the stage where a health condition has emerged and treatment is needed. In addition to medical interventions, individuals with chronic diseases can improve their outcomes through participating in support groups. External link

Public Health Resources for Adults with ACEs

- American Lung Association – Finding COPD Support External link

- American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association – Resources External link

- American Heart Association – Healthy Living External link

- American Diabetes Association – Living with Diabetes External link

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Connection – Recovery Support Groups External link

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration – Self-Help and Peer Support External link

- Peace Over Violence – Support Groups for Survivors of Violence External link

Sources:

1 DeQuattro, K., Trupin, L., Li, J., Katz, P. P., Murphy, L. B., Yelin, E. H., … Yazdany, J. (2019). Relationships between adverse childhood experiences and health status in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care and Research. Accessed on August 13, 2019. doi:10.1002/acr.23878 Return to anchor link

2 Suglia, S. F., Koenen, K. C., Boynton-Jarrett, R., Chan, P. S., Clark, C. J., Danese, A., … Zachariah, J. P. (2018). Childhood and adolescent adversity and cardiometabolic outcomes: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 137(5), 137:e15–137:e28. Accessed August 13, 2019. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000536 Return to anchor link

3 Cunningham, T. J., Ford, E. S., Croft J. B., Merrick M. T., Rolle I. V., Giles W. H. (2014). Sex-specific relationships between adverse childhood experiences and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five states. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 2014(9), 1033–1043. Accessed August 13, 2019. doi:10.2147/COPD.S68226 Return to anchor link

4 Huffhines, L., Noser, A., & Patton, S.R. (2016). The link between adverse childhood Experiences and Diabetes,” Current Diabetes Reports, 16(6), 54. Accessed August 13, 2019. doi:10.1007/s11892-016-0740-8 Return to anchor link

5 Ports, K. A., Holman, D. M., Guinn, A. S., Pampati, S., Dyer, K. E., Merrick, M. T., … Metzler, M. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences and the presence of cancer risk factors in adulthood: A scoping review of the literature from 2005 to 2015. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 44, 81–96. Accessed August 13, 2019. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2018.10.009 Return to anchor link

6 Cheong, E. V, Sinnott, C., Dahly, D., & Kearney, P. M. (2017). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and later-life depression: Perceived social support as a potential protective factor. BMJ Open, 7(9), 7:e013228. Accessed August 13, 2019. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013228 Return to anchor link

7 Loudermilk, E., Loudermilk, K., Obenauer, J., & Quinn, M. A. (2018). Impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) on adult alcohol consumption behaviors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 86, 368–374. Accessed August 13, 2019. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.08.006 Return to anchor link

The following section contains tabular data from the graphic in this post.

Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences

By Race

| ACE Category | White | Black | Hispanic | Multiracial | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional abuse | 35% | 28% | 36% | 49% | 30% |

| Physical abuse | 17% | 14% | 26% | 27% | 15% |

| Sexual abuse | 11% | 13% | 12% | 19% | 8% |

| Intimate partner abuse | 16% | 20% | 23% | 26% | 18% |

| Household substance abuse | 28% | 26% | 28% | 41% | 17% |

| Household mental illness | 28% | 26% | 28% | 41% | 17% |

| Parental separation or divorce | 26% | 43% | 30% | 39% | 19% |

| Incarcerated household member | 7% | 13% | 10% | 16% | 9% |

By Household Income

| ACE Category | $<15,000 | $15,000-24,999 | $25,000-34,999 | $35,000-49,999 | $≥50,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional abuse | 38% | 37% | 36% | 35% | 34% |

| Physical abuse | 26% | 22% | 19% | 19% | 15% |

| Sexual abuse | 17% | 13% | 13% | 12% | 10% |

| Intimate partner abuse | 25% | 23% | 19% | 18% | 14% |

| Household substance abuse | 33% | 32% | 30% | 28% | 25% |

| Household mental illness | 18% | 17% | 17% | 17% | 16% |

| Parental separation or divorce | 35% | 32% | 30% | 29% | 23% |

| Incarcerated household member | 13% | 11% | 9% | 8% | 5% |

Citation for this content: The MPH online program from Baylor University's Robbins College of Health and Human Sciences